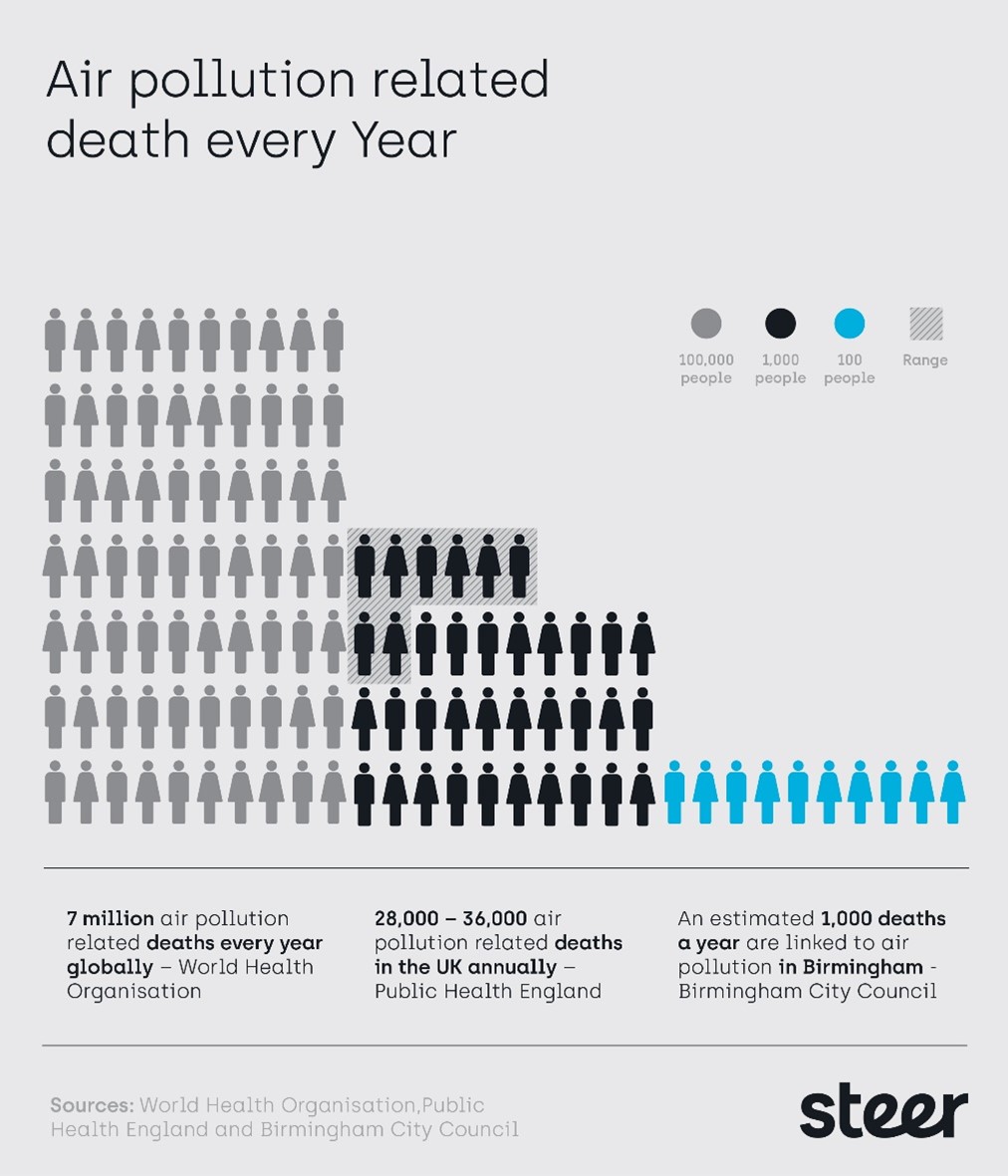

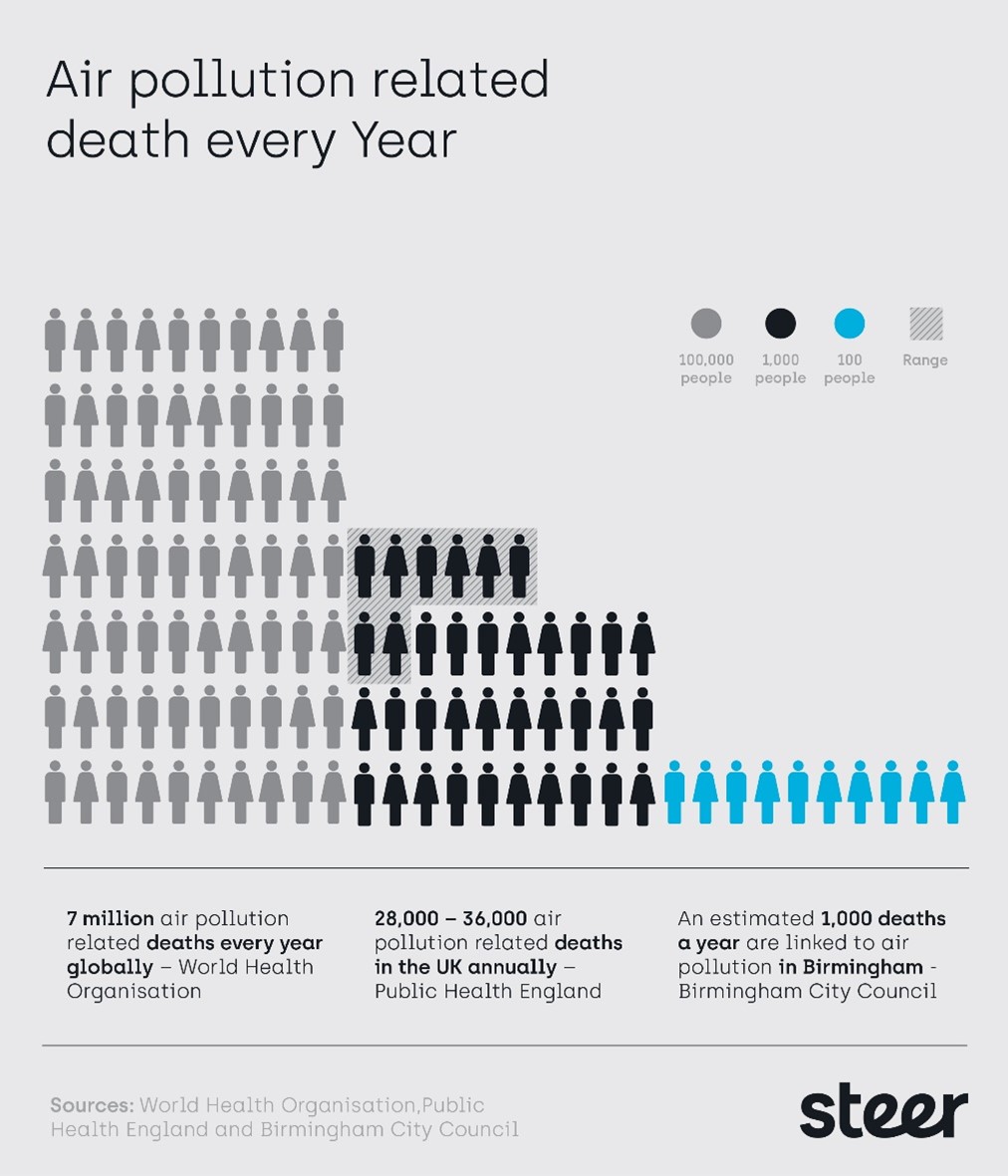

In 2021, an inquest into the death of a nine-year-old girl from London, Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, found that exposure to air pollution had made a “material contribution” to her fatal asthma attack. Making the ruling, the first of its kind in the UK, the coroner called for national air pollution limits in the country to be reduced in line with World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines.

Poor air quality is considered the biggest environmental threat to health in the world with Nitrogen Oxides (NO2), released from the exhaust pipes of vehicles, a huge driver of this health crisis. Today, the issue of how to improve air quality and health in a way that is both fair to road users and politically palatable is ever present, with pathways implemented from Outer London to Aberdeen.

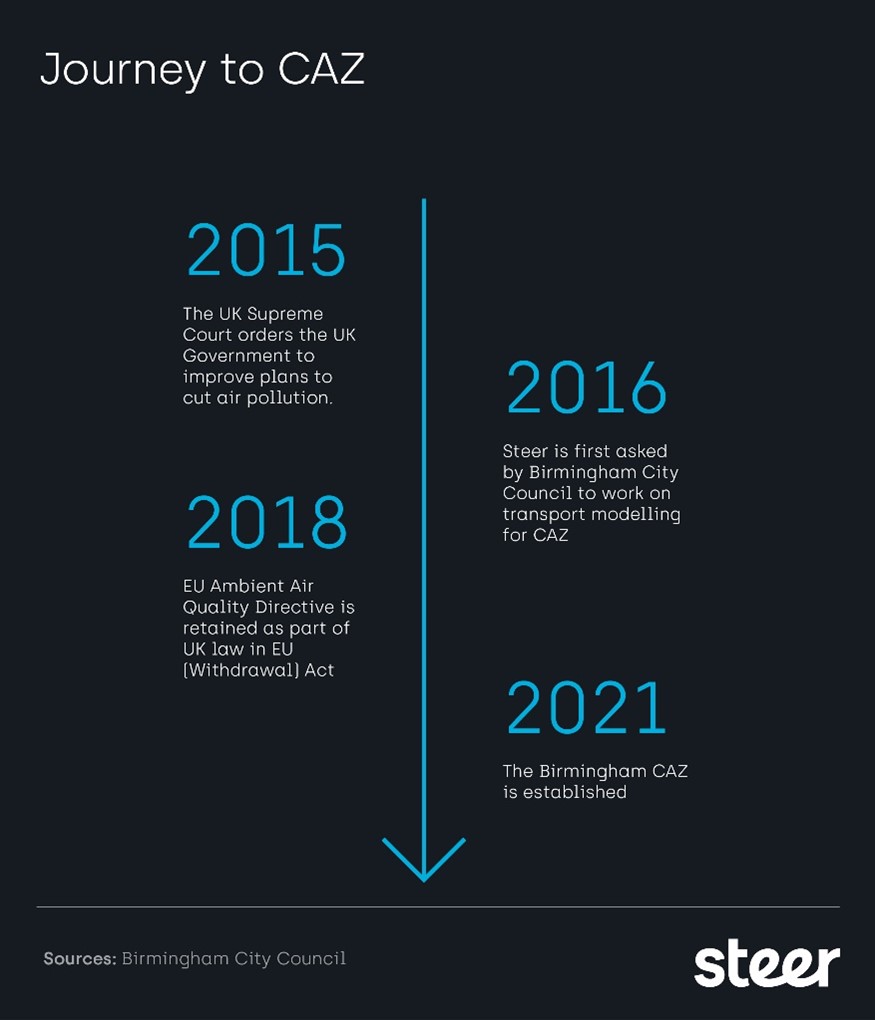

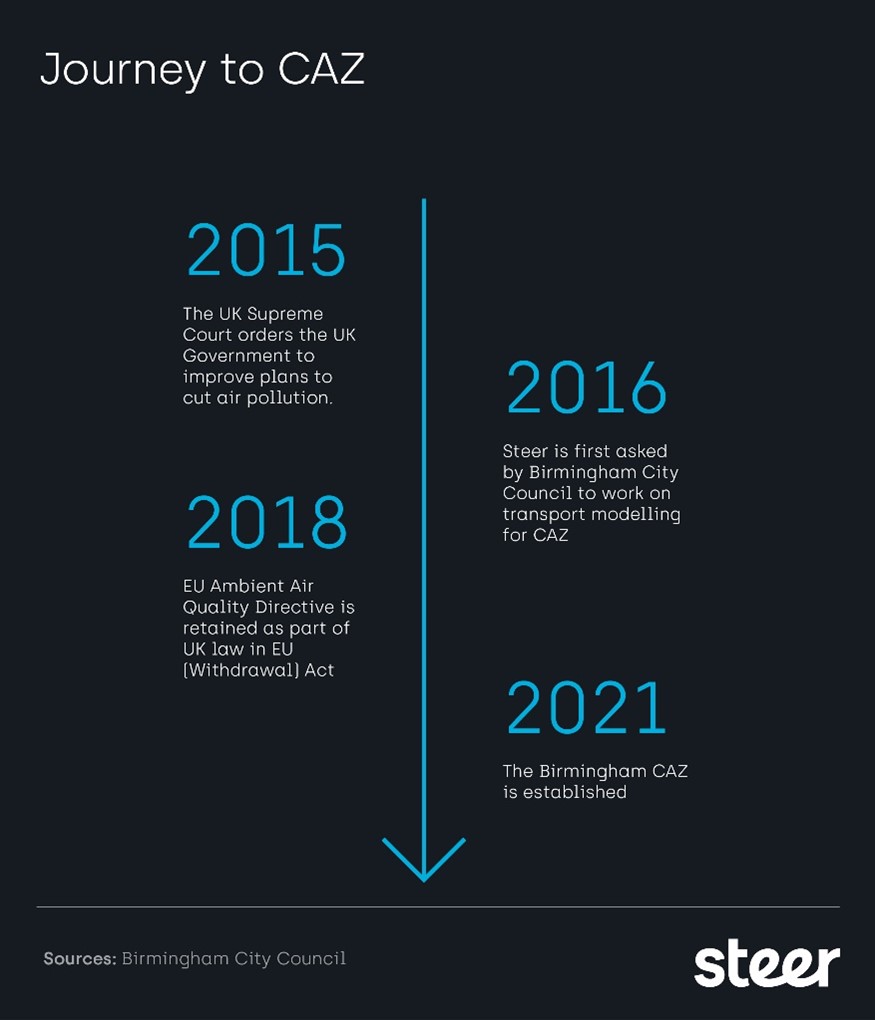

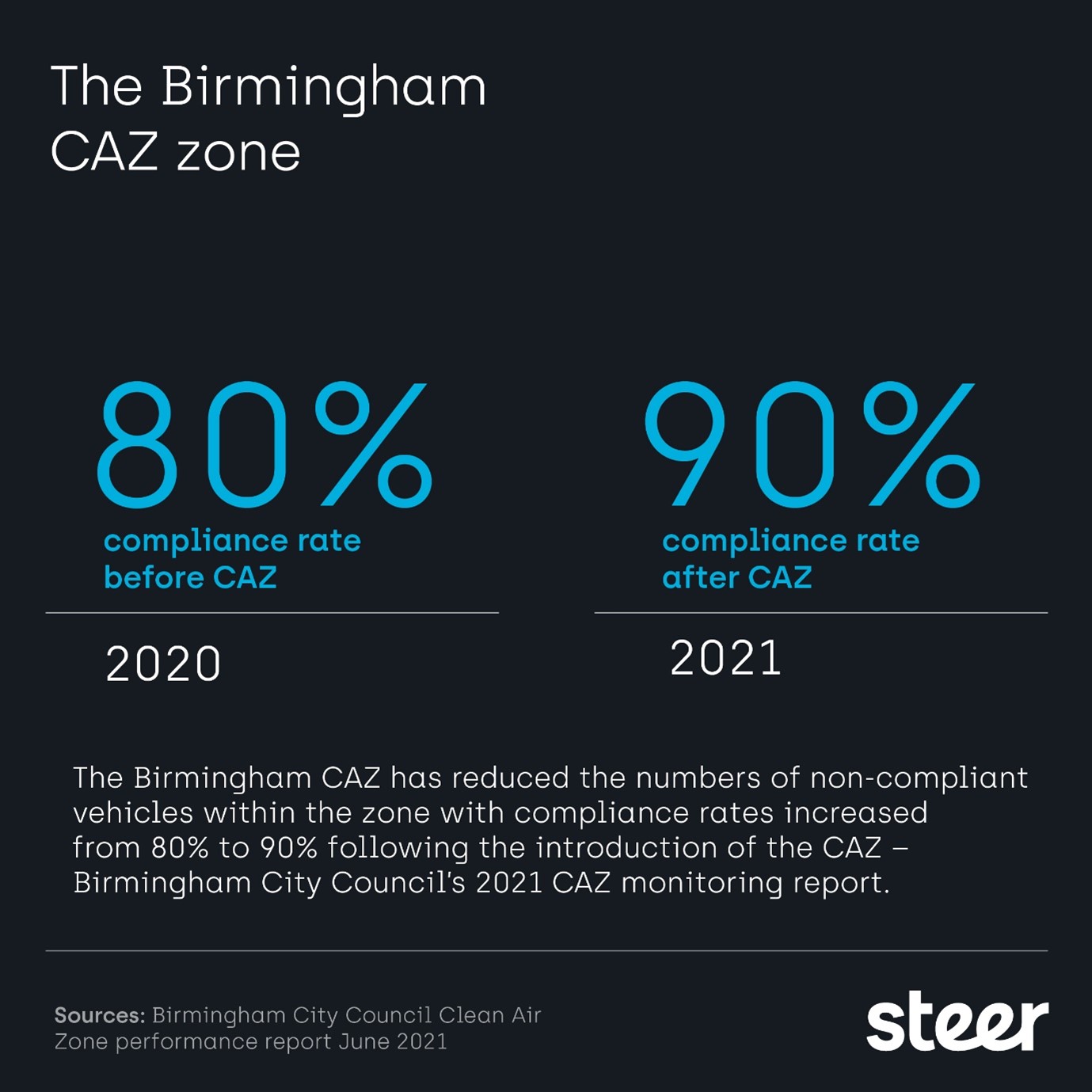

In 2016 Steer was enlisted by Birmingham City Council to develop a modelling methodology to support the development of a clean air zone (CAZ). Implemented in 2021, the Birmingham CAZ introduced fees for all vehicle types considered non-compliant with emission standards wishing to drive in the city centre.

Birmingham City Council already had an air quality (AQ) modelling team, but they needed Steer’s help to define the transport modelling required to deal with the complex demands of designing a CAZ.

The model would be used to produce output flows and speeds on road links to calculate NO2 emissions, which would then be put into specialist AQ software to calculate whether the NO2 concentrations are within legal limits.

“Birmingham was one of the first cities to be told by the Government that they had to come up with a plan to address poor air quality,” says Tom Caulfield, Principal Consultant at Steer.

“They were told this had to include transport modelling, but there was no clear framework for how to do it,” he continues.

“Birmingham was under pressure to deliver a workable solution. The model needed to be updated and run relatively quickly, but also needed to be robust and meet central Government’s evidence requirements”

Modelling for the future

Birmingham faces particular challenges when it comes to air pollution. The city’s post-World War II development included major highway construction (such as the A38, a major dual carriageway running through the centre of the city), and despite efforts in the region to address car dependency through investment in sustainable transport modes, the city remained a poor AQ hotspot.

To help tackle the problem, Tom needed to undertake innovative modelling that would supplement the existing PRISM and SATURN systems used by Transport for the West Midlands (TfWM). Although these models can examine mode shift, trip distribution, the highway system and public transport, they could not model compliant and non-compliant or potential behavioural responses to attendant road pricing from drivers as a CAZ requires.

Tom set about designing a transport modelling methodology which would address these shortcomings whilst making best use of both the pre-existing systems. The methodology needed to be cost-effective and agreeable to local and national governmental stakeholders.

“We had to come up with a methodology that central Government would sign off on,” he explains.

“We also had to account for an additional response where instead of choosing to change mode, destination or not to travel, drivers could choose to upgrade their vehicle,” says Tom.

Tom drew on his extensive experience working on strategic transport modelling both across the UK and internationally. Steer had already worked on a similar project, conducting a behavioural survey for Transport for London (TfL) supporting the extension of the Ultra Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ). In this case, a Stated Preference survey assessed existing road users' responses to the ULEZ fees, including whether they would upgrade their vehicle. Tom was able to draw on this, as well as other expertise from within Steer on demand modelling, road user fees, and behavioural research, to apply to Birmingham’s conditions.

The eventual model included predictions for both upgrading and the options those who didn’t upgrade would choose, namely mode shifting, changing route or continuing to drive into the zone and pay the fee. Prior to finalising the forecasts, the team completed a benchmarking study to ensure the results were in line with other studies in the UK and internationally.

“We had three key sources of information - PRISM, which gave us elasticities for non-compliant car users on whether they would avoid or pay the CAZ fee, SATURN that told us which route non-compliant through trips would divert to, and TfL’s behavioural survey that was used to inform whether users would upgrade their vehicle. This was combined to provide a single forecasting capability that could be updated quickly to test different CAZ scenarios.”

Steer was subsequently asked to carry out the transport modelling as part of a group of consultancies developing the Birmingham CAZ. Transport modelling was at the heart of the study, providing the essential inputs to air quality modelling, optioneering, cost-benefit analysis and revenue forecasting.

Implementation: Realities on the ground

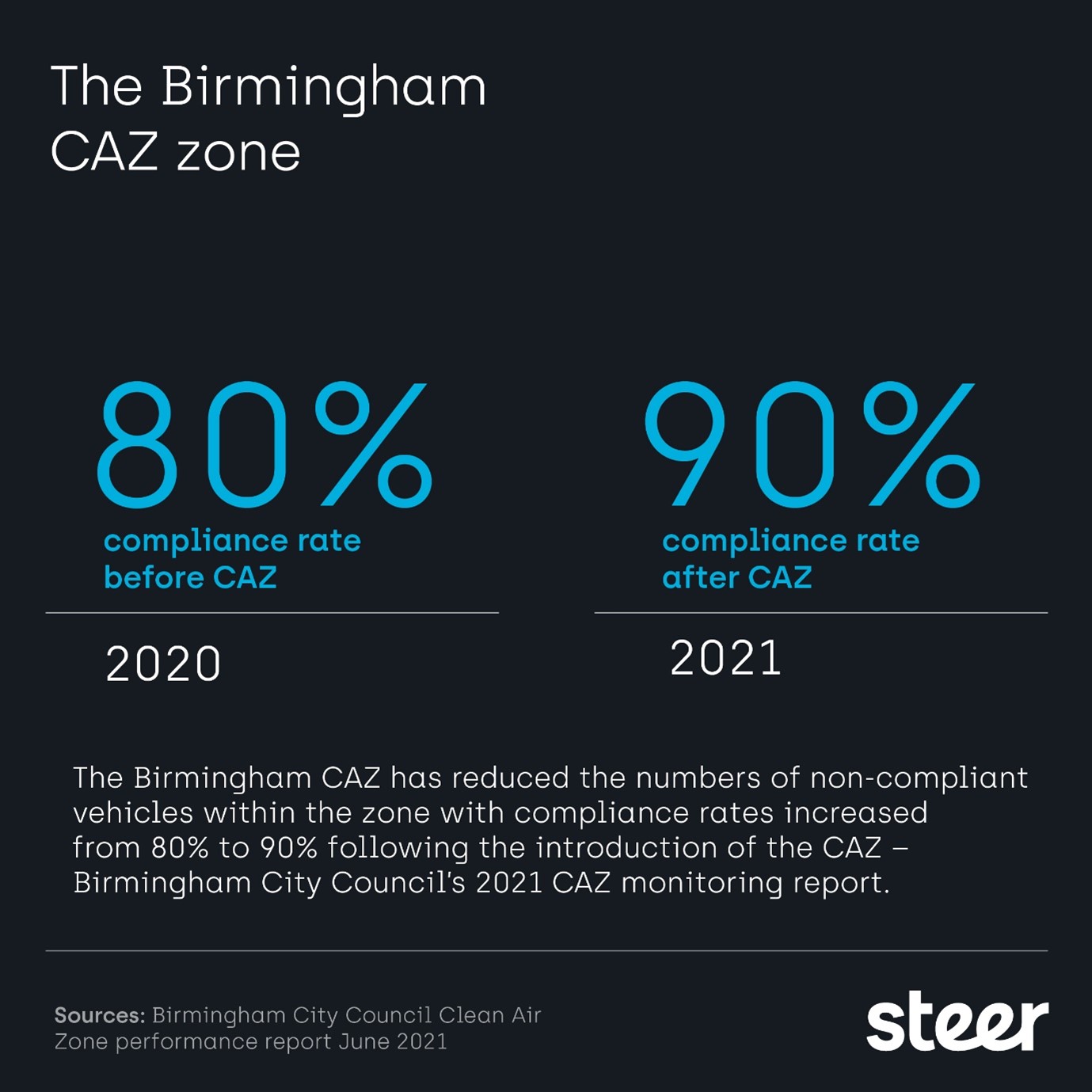

Steer initially modelled two different CAZ options for Birmingham City Centre, where the majority of NO2 exceedances are located. These looked at making all non-compliant vehicle types pay and another option excluding cars.

The resulting transport and air quality modelling provided strong evidence that due to the severity of pollution and the high proportion of cars in the city centre, a wide range of vehicles would need to face a fee, including cars, taxis, vans, heavy goods vehicles, and buses.

“We also needed to understand the impact at different payment levels to help Birmingham decide what cost they should apply,” adds Tom.

“There was strong political leadership to produce a plan to reduce exceedances to legal levels in the shortest possible time,” says Tom.

“They wanted to improve the health of residents and visitors to the city. However, they understood the financial difficulties these payments would have on some people and businesses.

“Once the leadership saw the results they understood that a CAZ was needed and pushed forward developing the scheme. However, this included supporting policies such as exemptions and a scrappage scheme to reduce the financial burden on more economically vulnerable users,” says Tom.

Since completing the Birmingham project, Steer has continued to be engaged in Clean Air Plans (CAP), helping areas around the UK with this pressing environmental and health problem. To find out more about how Steer can help with your CAP and our other groundbreaking work in air quality contact Elaine Meskhi.

To find out more about our wider sustainability offer, contact Serbjeet Kohli.